Symphysis Pubis Dysfunction (SPD)

Symphysis Pubis Ligaments

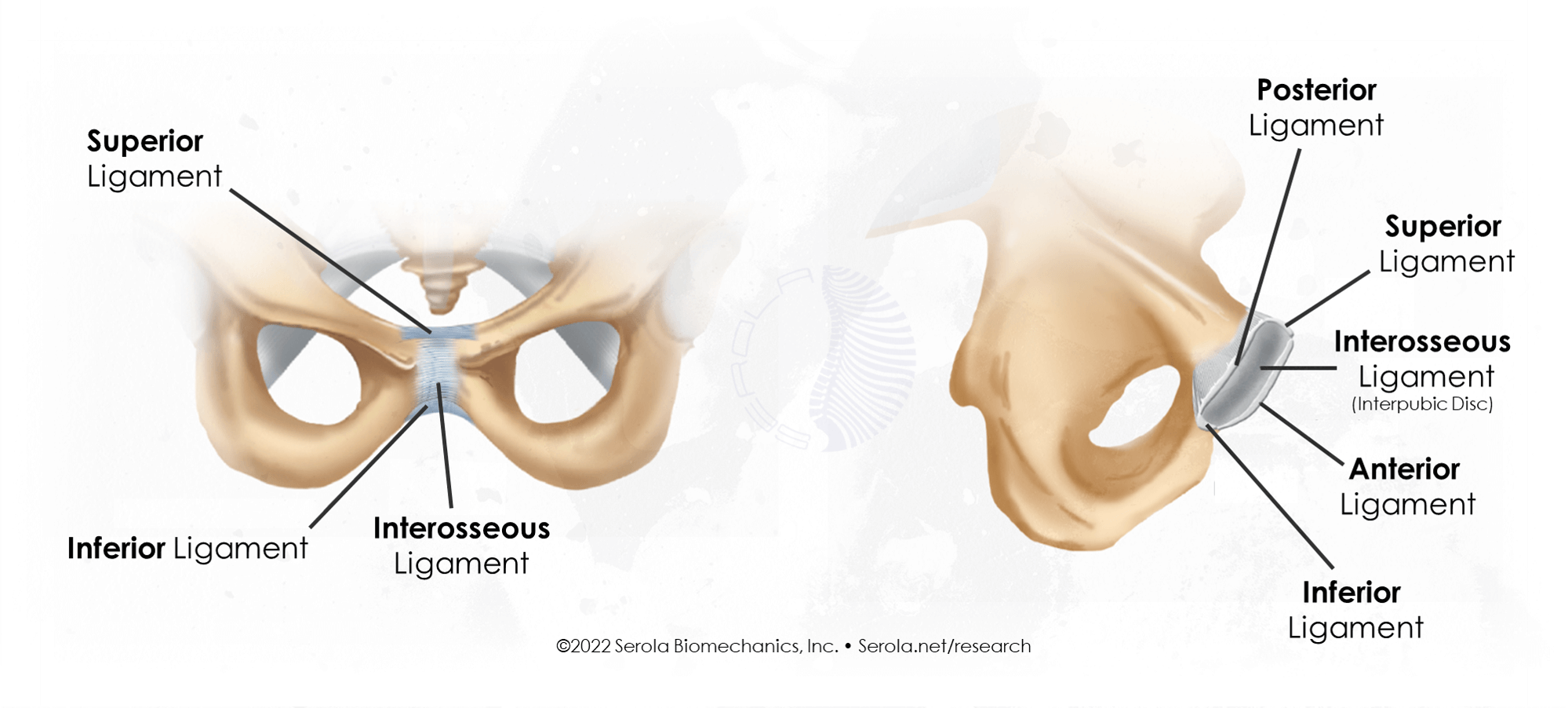

Like the ligamentous region of the sacroiliac joint, symphysis pubis is a syndesmosis and is composed of five ligaments:

– Superior pubic ligament connects the superior part of the joint

– Posterior pubic ligament (Arcuate ligament) connects the inferior part of the joint

– Anterior pubic ligament

– Posterior pubic ligament

– Interosseous ligament (Interpubic disc) separates and connects the opposing surfaces much like the interosseous ligament in the sacroiliac joint

The pelvis consists of a triad of three joints; two sacroiliac joints and one symphysis pubis, which interconnect to provide stability and motion to the pelvis. Like the two sacroiliac joints, the symphysis pubis is a weight bearing joint that is responsible for force transfer between the upper and lower body. As part of our core structure, its stability is important to normal functioning of the entire body.

How Symphysis Pubis Dysfunction happens

Although trauma from accidents or contact sports may cause SPD, the most common cause is related to pregnancy. During the later stages of pregnancy, as the baby drops lower in the belly, the pressure increases on the symphysis pubis, and may lead to pain or discomfort. Symptoms may include pain directly at the symphysis and/or pain in the groin, buttocks, or down the inside of the leg. It may spread to the lower back and/or perineum. The pain may feel like a mild pinch or ache or be bad enough to limit your ability to walk. There may be a clicking sound near the pelvic area while moving your legs or walking.

Usually, the symphysis pubis has a normal gap of 4-5 mm (filled with the disc) to an additional 2-3 mm during pregnancy, for a total separation of not more than 9 mm. If it widens farther, it becomes unstable and dysfunctional.

Ligamento-muscular Reflex

Within every ligament are nerve receptors that send signals to the brain that can be interpreted as pain. Other nerve receptors go indirectly to the muscles around the pelvis, and control the tone (tightness) of these muscles. As in any joint, the ligaments in the symphysis pubis respond to injury by activating the muscles to either tighten or loosen in order to take pressure off the injured ligaments; this is called the ligamento-muscular reflex. The injury is usually not due to a blow but, rather, an overstretching of the ligaments, and occurs in about 1/3 of pregnancies.

During the latter stages of pregnancy, as the baby descends, the hormone relaxin softens the ligaments and cervix to allow the symphysis pubis to spread. Normally, it spreads at a rate which doesn’t overstress the pubic ligaments, so the muscles remain balanced and pain free. But, in some situations, such as carrying the baby too far forward, an overweight mother, pushing too hard during labor, having a very large baby, or SPD in a previous pregnancy, the symphysis pubis may spread too fast for the nerve receptors to adapt in a timely manner, and the ligaments sprain.

In this case, the nerves call out the muscles to help. The muscles respond by contracting in an attempt to hold the joint within normal limits, or maintain a rate of opening that will not overstress the ligaments of the symphysis pubis. In addition to the pain in the sprained ligaments themselves, the muscles produce pain when they are tight for prolonged periods due to reduced circulation, and may also produce pain at their attachments to the pelvis or legs.

Additionally, the other end of the muscles pull on the pelvis, trunk, and legs and alter their position and movement patterns. We may see the mother-to-be with waddling gait, arched back, anterior pelvic tilt, and back, groin, hip and leg pain, with difficulty walking or standing for prolonged periods.

Relation to Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction

Whenever you have sacroiliac dysfunction, always be aware that the symphysis pubis may become dysfunctional as well, and vice versus. As part of the triad of pelvic joints, sacroiliac dysfunction will directly affect the symphysis pubis. When one sacroiliac joint is too loose, the other one is relatively fixed. This imbalance alters the movement pattern of the symphysis pubis, and is magnified during and after pregnancy. Rather than move in a smooth reciprocating pattern, it responds to the mismatched sacroiliac joints by twisting excessively. Some parts of the ligaments within the symphysis pubis become overstressed and painful, which results in activation of the ligamento-muscular reflex. Ligaments have a direct connection to the muscles that move the joint[1]. As a result, some of the muscles that attach to the pelvis also become tight and painful.

Diagnosis

Although there is no definitive diagnostic test for Symphysis Pubis Dysfunction, Leadbetter et al.[2] developed a scoring system, using symptoms that were significantly associated with Symphysis Pubis Dysfunction, including pubic bone pain on walking, turning over in bed, climbing stairs, standing on one leg, and previous damage to back or pelvis. They stated that the presence of any two of them was considered diagnostic of SPD, and provided a monitoring system to facilitate screening, diagnosis, management and success of various interventions. Their advice is to pay attention to these symptoms and evaluate your progress with them.

Treatment

The key to limiting pain due to symphysis pubis dysfunction is to limit the stress on the ligaments. You can do this by limiting the rate of opening and the overall width of the symphysis pubis. By keeping the symphysis pubis within normal range of motion, the ligaments are not stressed and have no need to tense the muscles. Physiologically, for pregnant and postpartum women, I suggest that normal range of motion should not be defined only in millimeters, but also by whether the ligaments are stretched to the point where they activate the ligamento-muscular reflex; this can be recognized by pubic tenderness or pain and/or pelvic, back, or leg muscle tightness. Rest, postural awareness, and a pelvic belt are recommended as the safest and most beneficial methods of treatment for SPD[3].

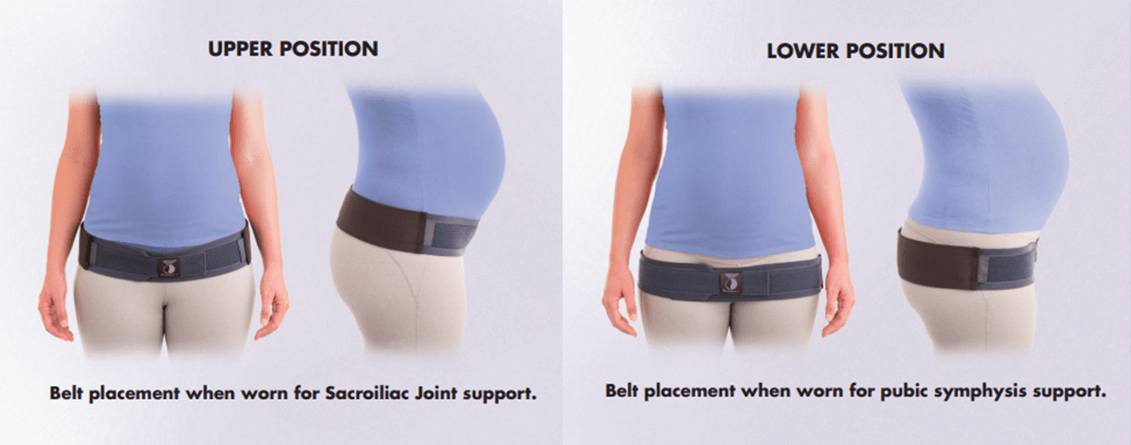

The simplest and most effective way to limit the expansion of the symphysis pubis is with a sacroiliac belt (also known as a pelvic belt or trochanter belt). Various studies have shown differences in the belt’s effect on the sacroiliac joint or symphysis pubis by where the belt is placed on the pelvis, in either the upper or lower position. The upper position has been shown to be more effective for the sacroiliac joints, while the lower position is more effective for the symphysis pubis.

The landmark to look for is the front leg crease that is found at the bottom of the pelvis when raising one leg. The upper position is determined by placing the lower edge of the belt along this crease. The lower position is found by placing the upper edge of the belt along this crease. The lower position will go directly on and compress the tops of the leg bones (trochanters). A video showing proper position and placement of the Serola Belt during pregnancy can be found here: https://serola-wp.perrill.dev/research-category/pregnancy/serola-belt-pregnancy-instructions/

Sometimes, during childbirth, when the symphysis pubis widens for delivery, it may misalign and not return to its proper position, and cause pain and dysfunction long after postpartum. This may affect subsequent pregnancies, as well. In many cases, a properly made sacroiliac belt will help compress and guide the symphysis pubis, and sacroiliac joints, into proper alignment.

Do’s and Don’ts for Symphysis Pubis Dysfunction

– Don’t squat.

– When getting in or out of car, keep your knees together. Back in, sit, and then turn.

– Do keep a pillow between your knees while in bed.

– When turning over in bed, keep your knees together.

– Don’t turn too quickly or twist excessively while turning over in bed.

– Be careful climbing stairs.

– Don’t exercise on a bicycle or stair stepper.

– Do mild exercise in water.

– Do use a pillow to support your lower back while sitting or riding in a car.

– Sit evenly on both sit bones.

– Don’t cross your legs.

– Don’t sit or stand for prolonged periods.

– Be careful bending, lifting and twisting.

– Don’t perform tasks that involve twisting, like vacuuming, raking, sweeping, or mopping.

– Don’t put a heavy weight in one hand or on one leg, e.g., carrying a child on your hip.

While a few of the above may also be recommended for a normal postpartum, it should be noted that the above cautions are for painful and/or dysfunctional symphysis pubis.

Other Peer-reviewed Studies on the Symphysis Pubis

Range of Motion

In a study of 4 cadavers and 15 healthy volunteers, Walheim et al. [4] found movements of the symphysis pubis were small. Vertical translations averaged around 2.5 mm, while transverse and sagittal translations were less than 1mm. Rotation in the frontal and sagittal planes were also less than 1 mm with rotations up to 3 degrees. No significant differences were noted between the males and females except for the pregnant women, which were more mobile.

Symphysis Pubis Dysfunction

Classical findings of pubic symphysis syndrome include pubic gaping, pain associated with walking, tenderness, crepitus, excessive motion upon pressure, and external rotation of the acetabula [5, 6 ], leading to a waddling gait.

Callahan [5] further stated that “Even 3 to 5 cm separations cannot be considered as true ruptures in the absence of clinical symptoms. Generally, however, separations of 1.0 cm or over are considered to be symptom producing.” He promotes diagnosis of pubic separation through signs and symptoms rather than the use of x-rays, claiming that separation of the pubis is rare, occurring in about 1 in 2,000 women during, or after, delivery. In those cases, he says that strapping the pelvis with a pelvic belt is usually sufficient treatment.

However, Chamberlain [7], recognizing the interrelationship of the symphysis pubis and the sacroiliac joint developed a series of 5 x-ray procedures that uses variations in height of the two sides of the symphysis pubis as a diagnosis of “sacroiliac slip”. Some authors currently regard this technique as the only x-ray method to accurately measure sacroiliac dysfunction.

Using two of Chamberlain’s procedures, the single leg stance compared to double leg stance, but with a with a more controlled study population, Garras [8] found translation at the symphysis pubis to average 1.4 mm for men, 1.6 mm for nulliparous women, and 3.1 mm for multiparous women.

The symphysis pubis joint and sacroiliac joints are interdependent and function as a unit [9, 10]. Berg et al. [11] found that “Symphysiolysis was significantly more common among women with dysfunction of the sacroiliac joints than among pregnant women without backache, supporting earlier suggestions that hormonal effects are an important cause of instability in the pelvis.”

Bellamy [12] stated that “The most reliable clinical sign of instability of disruption of the SI joint is that of disruption of the pubic symphysis.”

References:

1. Hilton, J., On Rest and Pain: A Course of Lectures on the Influence of Mechanical and Physiological Rest in the Treatment of Accidents and Surgical Diseases, and the Diagnostic Value of Pain. 2nd Edition ed. 1891, Royal College of Surgeons of England in the years 1860, 1861, and 1862: P.W. Garfield.

2. Leadbetter, R.E., D. Mawer, and S.W. Lindow, The development of a scoring system for symphysis pubis dysfunction. J Obstet Gynaecol, 2006. 26(1): p. 20-3.

3. Nilsson-Wikmar, L., et al. Effects of Different Treatments on Pain and on Functional Activities in Pregnant Women with Pelvic Pain. in Third Interdisciplinary World Congress on Low Back Pain & Pelvic Pain. 1998. Vienna, Austria.

4. Walheim, G., S. Olerud, and T. Ribbe, Mobility of the pubic symphysis. Measurements by an electromechanical method. Acta Orthop Scand, 1984. 55(2): p. 203-8.

5. Callahan, J.T., Separation of the symphysis pubis. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 1953. 66(2): p. 281-93.

6. Taylor, R.N. and R.D. Sonson, Separation of the pubic symphysis. An underrecognized peripartum complication. J Reprod Med, 1986. 31(3): p. 203-6.

7. Chamberlain, W.E., The Symphysis Pubis in the Roentgen Examination of the Sacroiliac Joint. American Journal of Roentgenology and Radium Therapy, 1930. 24(6): p. 621-625.

8. Garras, D.N., J.T. Carothers, and S.A. Olson, Single-leg-stance (flamingo) radiographs to assess pelvic instability: how much motion is normal? J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2008. 90(10): p. 2114-8.

9. Levangie, P. and C. Norkin, Joint Structure and Function. A Comprehensive Analysis. 2005, Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis Company.

10. Vleeming, A., et al., An integrated therapy for peripartum pelvic instability: a study of the biomechanical effects of pelvic belts. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, 1992. 166(4): p. 1243-7.

11. Berg, G., et al., Low back pain during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol, 1988. 71(1): p. 71-5.

12. Bellamy, N., W. Park, and P. Rooney, What Do We Know About the Sacroiliac Joint. Seminars in Arthritus and Rheumatism, 1983. 12(3).